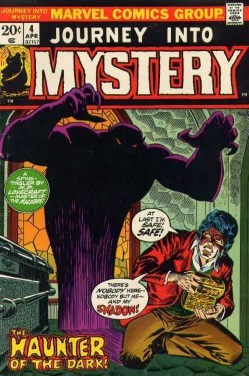

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Haunter of the Dark,” written in November 1935 and first published in the January 1936 issue of Weird Tales.

It’s a sequel of sorts of Robert Bloch’s “Shambler From the Stars” (not available online, and reading it isn’t necessary to appreciate “Haunter”), and Bloch later wrote “The Shadow From the Steeple” as a follow-up. You can read “Haunter” here.

Spoilers ahead for all three stories.

“This stone, once exposed, exerted upon Blake an almost alarming fascination. He could scarcely tear his eyes from it, and as he looked at its glistening surfaces he almost fancied it was transparent, with half-formed worlds of wonder within. Into his mind floated pictures of alien orbs with great stone towers, and other orbs with titan mountains and no mark of life, and still remoter spaces where only a stirring in vague blacknesses told of the presence of consciousness and will.”

On his first trip to Providence, Robert Blake visited an old man who shared his occult obsessions—and whose mysterious death ended the visit. Nevertheless, in 1934, Blake returns to create weird literature and art.

He sets up shop on College Hill. From his west-facing windows he overlooks the city, splendid sunsets, and the “spectral hump” of Federal Hill, a “vast Italian quarter” so avoided by his acquaintances it might as well be the unreachable world his imagination paints it. One structure intrigues him: a huge deserted church with a tower and tapering steeple. Birds avoid the tower, wheeling away as in panic.

Finally he ventures up Federal Hill. No one will direct him to the deserted church, but he finds it: a blackened fane atop a raised lot. Spring hasn’t touched it; the surrounding vegetation is as lifeless as the neglected edifice. A policeman tells Blake the church has stood unused since 1877, when its outlaw congregants fled following the disappearance of some of their neighbors. This heightens Blake’s sense of the church’s evil, and lures him inside through a broken cellar window.

Though dust and cobwebs reign, he discovers a vestry room stocked with such eldritch tomes as the Necronomicon and De Vermis Mysteriis! Well-read cultists, these Starry Wisdom chaps. He also finds a record book in cryptographic script, which he pockets. Next he explores the tower. At the center of its summit chamber, a pillar supports an asymmetrical metal box containing a red-striated black crystal. As Blake stares, his mind fills with visions of alien worlds, and of cosmic depths stirring with consciousness and will.

Then he notices a skeleton clad in decayed 19th century clothing. It sports a reporter’s badge and notes about the Starry Wisdom cult suggesting the Shining Trapezohedron can not only serve as a window on other places—a Mythos palantir!—but can summon the Haunter of the Dark.

Blake supposes the reporter succumbed to heart failure, though the scattered and acid-eaten state of his bones is perplexing. Gazing again into the Trapezohedron, he feels an alien presence, as if something were gazing back. Does the crystal glow in the waning light, and when he snaps the lid shut over it, does something stir in the windowless steeple overhead?

Blake takes off. Back on College Hill he feels increasingly compelled to stare at the church. He also deciphers the record book. It confirms the Shining Trapezohedron is a window on all time and space, and describes the Haunter as an avatar of Nyarlathotep which can be dispelled by strong light. Hence, Blake fears, the stirring he heard in the steeple after he inadvertently summoned the god by closing the box, plunging the crystal into darkness.

Thank saner gods for the streetlights between his home and the church! The Haunter may invade his dreams, but can’t physically visit. It does try to make him sleepwalk back to its lair, but after waking in the tower, on the ladder to the steeple, Blake ties his ankles every night.

He doesn’t reckon on thunderstorms and power failures. During one outage, neighbors hear something flopping inside the church. Only by surrounding the fane with candles and lanterns do they prevent the monster’s egress. In dreams, Blake feels his unholy rapport with the Haunter strengthen; waking, he feels the constant tug of its will. He can only huddle at home, staring at the steeple, waiting.

A final thunderstorm hits. The power goes out. The neighborhood guard around the church blesses each lightning flash, but eventually these cease and wind extinguishes their candles. Something bursts from the tower chamber. Unbearable foetor sickens the crowd. A cloud blacker than the sky streaks east. On College Hill, a student glimpses it before a massive lightning strike. Boom, an upward rush of air, a stench.

The next day Blake’s found dead at his window, face a rictus of terror. Doctors suppose some anomalous effect of the lightning must have killed him. But a superstitious Dr. Dexter heeds the dead man’s last frenzied jottings, which claim he began to share the alien senses of the Haunter as its mind overwhelmed his. Blake feared it would take advantage of the power failure to “unify the forces.” There it is, his last entry cries: “hell-wind—titan blur—black wings—the three-lobed burning eye….”

Dr. Dexter recovers the Trapezohedron not from the church’s tower room but from the lightless steeple. He throws it into the deepest channel of Narragansett Bay. So much for you, Haunter. Or, um, maybe not so much?

What’s Cyclopean: The dark church! We also get “a spectral hill of gibbering gables.” How, pray tell, do gables gibber?

The Degenerate Dutch: Somehow Providence’s Italian quarter is an “unreachable” land of mystery. And of course, not one of Blake’s friends has ever been there. This is kind of like living in DC and boasting that no one you know has visited Anacostia: plausible but it doesn’t say anything great about you, and maybe your friends should get out more. Lovecraft also tries to run with the “superstitious foreigners” trope in spite of the ‘superstitions’ being totally accurate and practically useful.

Mythos Making: The trapezohedron passes through the grasping appendages of Outer ones, Old Ones, Valusian Serpent Men, Lemurians, and Atlantians before Nephren-Kha builds its temple in Khem. Blake seems pretty familiar with the Mythos pantheon, not only recognizing the Standard Scary Bookshelf in the church but praying variously to Azathoth and Yog-Sothoth while trying to avoid Nyarlathotep.

Libronomicon: “Haunter” includes two sets of texts. First up are Blake’s stories: “The Burrower Beneath”, “The Stairs in the Crypt”, “Shaggai”, “In the Vale of Pnath”, and “The Feaster from the Stars.” Some are based on Robert Bloch Stories (for “Feaster” read “Shambler” and get this story’s prequel), while others will be borrowed by later Lovecrafters (e.g., Brian Lumley’s The Burrowers Beneath). Then in the old church we have several infamous volumes: the Necronomicon, Liber Ivonis, Comte d’Erlette’s Cultes des Goules, Unaussprechlichen Kulten, Prinn’s De Vermis Mysteriis, the Pnakotic Manuscripts, and the Book of Dzyan.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Blake’s supposed madness is used by “conservative” commentators to explain away the events around his death.

Anne’s Commentary

And yet again, Lovecraft treats a friend to fictional death. This time, however, he’s just returning the favor. A very young Robert Bloch asked the master’s permission to kill off his literary avatar in the 1935 “Shambler from the Stars.” Not only did Lovecraft grant permission, but he volunteered a Latin translation for Bloch’s invented tome, The Mysteries of the Worm, which debuted in “Shambler” and which we now know and love as Ludvig Prinn’s despicable De Vermis Mysteriis.

“Shambler” is a straightforward tale of inadvertent summoning: The youthful Blake approaches an older occultist with Prinn’s book. Older But Not Wiser gets so into translating the Latin aloud that he launches right into a spell for calling down a servitor from beyond the stars. It comes, invisible but tittering, and drains the old fellow’s blood. As the crimson libation permeates its system, it becomes visible, a jelly-like blob waving tentacles and talons. Blake escapes, the house burns down, no evidence against him.

But Blake gets his in Lovecraft’s rejoinder, this week’s story. Not to be forever silenced, Bloch wrote a sequel to the sequel in 1950, “The Shadow from the Steeple.” It takes up a question Lovecraft leaves to the acute reader: If one wants to avoid plunging the Trapezohedron into darkness, does tossing it into the deepest depths of Narragansett Bay make sense? No, it doesn’t, Bloch tells us, for that freed the Haunter to take over Dr. Dexter’s mind and body. In an atomic age twist, Dexter turns from medicine to nuclear physics and helps develop the H-bomb, thus ensuring the destruction of mankind. Huh. You’d think Nyarlathotep could destroy humanity without going through all that trouble, but maybe he enjoyed the irony of watching it self-destruct?

Anyhow, much of the story is a tedious recap of “Haunter,” followed by a tedious recap of the hero’s sleuthing into the mystery of Blake’s death, followed by a kind of amusing denouement between hero and Dexter. Hero tries to shoot Dexter, but Dexter glows at him in the dark, which somehow kills hero. Radiation poisoning? Whatever. The best part of the story is the conclusion. We’ve learned at the start of the story that two black panthers have recently escaped from a traveling menagerie. As Dexter strolls his night-shrouded garden, the panthers come over the wall. In Lovecraft’s sonnet “Nyarlathotep,” nations “spread the awestruck word, that wild beasts followed him and licked his hands.” And so they lick Dexter’s, while he turns his face “in mockery” to the watching moon.

I find the less successful Mythos stories lose Lovecraft’s sense of awe, rendering the inscrutable all too scruted. Whereas “Haunter” dwells with affection on the mysteries dimly revealed to Blake, first in the Trapezohedron and then in the vast mind and memory of its master. “An infinite gulf of darkness, where solid and semi-solid forms were known only by their windy stirrings, and cloudy patterns of force seemed to superimpose order on chaos and hold forth a key to all the paradoxes and arcana of the worlds we know.” Now that’s some cosmic wonder for you, the more compelling for its pointed vagueness. And what does kill Blake, after all? The ultimate lightning blast doesn’t even crack his window. Could it really have communicated itself to him through the unharmed glass, or does he die because he has merged at last with the Haunter and so must be dispelled along with it?

“Haunter” is one of Lovecraft’s last forays into his Mythos, almost his final meditation on man’s paradoxical drive to know and terror of learning too much; for all its in-joking, its tone remains sober. Is Eden’s apple sweet but poisonous, or is it sweet and poisonous, because the pleasure and the pain can’t be separated? Written in the same year, “The Shadow Out of Time” dwells at much greater length on the question. Knowledge shakes Peaslee, its protagonist, but doesn’t kill him; even after his discoveries in Australia, he can wonder whether his Yithian “ordeal” wasn’t the greatest experience of his life. Poor Blake. He never has a chance to get over the terror. But then again, his counterpart did sic that star vampire on poor Howard, and payback’s a bitch.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

This is the last of Lovecraft’s solo stories, written a little over a year before his death. Lovecraft got his first professional publication at age 31, and died at 46—a short, prolific career, with quality still rising at the end and no sign that he’d hit his peak. Occasionally I’m reminded that if he’d had longer, 90% of his existing stories would have been seen as the sort of early work that usually makes for filler in an author’s later collections. That makes it even more impressive that so much is good (or at least engaging) and wildly original. I’m certainly not the first person to wonder what he would have produced at 50 or 60. Or to consider that his work probably survived through years of obscurity to its current prominence, not solely on its own (very real) merit, but due to his mentoring and his willingness to fling his sandbox wide open for others to play in.

“Haunter” has the quality I expect from these later stories—good integration of description with action, detailed worldbuilding, a central premise that successfully combines temptation and horror. And it manages to stay close to the action even with the usual third-hand framing conceit. That said, I found it a bit of a let down by comparison with some of his other late work—although only by comparison. “Whisperer in Darkness,” “At the Mountains of Madness,” “Shadow Out of Time,” and even “Shadow Over Innsmouth” look in-depth at alien/esoteric cultures and do serious heavy lifting for a more cohesive Mythos, while Haunter hangs a big part of its effect on familiarity with that back story. Still, the shining trapezohedron is awesome—I want one, you know you do too—and much of my complaint is that we don’t get more detail on what can be seen through it. I don’t want everything revealed, but I do want alien worlds, glimpses of the Starry Wisdom Cult’s rituals—and relative to those other stories, Haunter seems short on their details. I could have seen a lot more and still felt like he was leaving a fair amount to the imagination.

I’m not the only one who wants more, and many folks seem to have gone ahead and made it themselves. Aside from Bloch’s sequel, “Haunter” is back story for the Illuminatus Trilogy. The Church of Starry Wisdom appears to have a branch in Westeros. And other branches several places online. I did not click through because I’m not an idiot. The Shining Trapezohedron itself is given to the winner of the Robert Bloch Award. Which I now want, because I’m an idiot.

Of course, everyone wants the trapezohedron. Who wouldn’t? Alien worlds and cosmic secrets? It’s like the Asguardian tesseract and a palantir rolled into one—not surprising as one suspects it of being grand-daddy to both. As with many of Lovecraft’s other late stories, “Sign me up!” seems like an inevitable refrain. The trapezohedron has an interesting pedigree, too—Made With Love in the Workshops of Yuggoth. That fits the Outer One’s special relationship with , and propensity to evangelize for, Nyarlathotep. And we see here, as in “Whisperer,” Lovecraft’s terror that wanting to better understand anything foreign—Italian or Yuggothi—is a temptation most strenuously to be avoided.

Back on Earth, this story is one last love letter to Providence, more compelling than “Charles Dexter Ward.” In “Ward,” the paeans to the city and the verbal maps seem a touch dissociated from the actual action. Here, everything focuses on the contrast between city as comforting home and city as alien horror. So many things can make your beloved home dangerous and unfamilair. You go into the wrong area and realize you don’t know the place at all, or the power goes out, and suddenly it’s not your safe, comforting haven after all. And the fact that it always balances on that edge, and could easily tilt over from comfort into horror, is one of the things that makes you love it—always apocalypse just around the corner.

The ending is ambiguous, and I think it works. I’m left wondering—did the Haunter possess him and then get caught by lightning, as some have suggested? Has Blake’s mind been torn from his body to travel the void shown by the trapezohedron? That seems like something a Yuggothi artifact would do. Has he been killed outright as sacrifice, or punishment? Inquiring minds want to know—and that, the story suggests, is the real danger.

Next week, we return to Kingsport to explore “The Strange High House in the Mist.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.